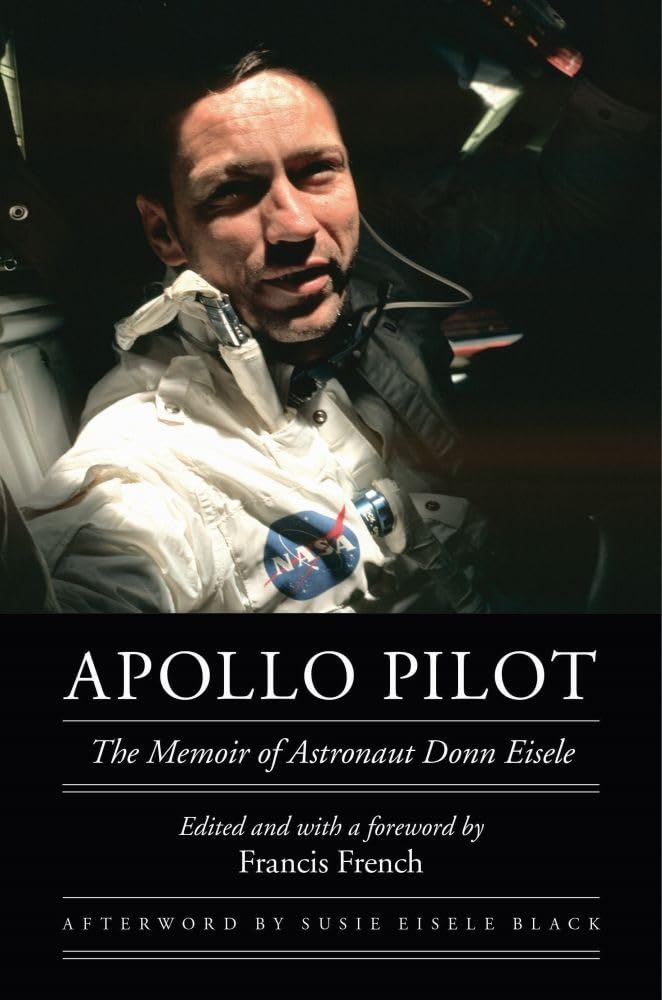

Apollo Pilot by Donn Eisele

We were insolent, high-handed, and Machiavellian at times. Call it paranoia, call it smart—it got the job done. We had a great flight. Anything less might have meant the end of the program. And I’d rather be called a shithead and live through it than have everybody remember what a nice guy I was.

—Donn Eisele, Apollo 7 Command Module Pilot

After the tragic Apollo 1 fire, NASA’s lunar program appeared to stall for more than a year. Engineers were still hard at work behind the scenes fixing the command module (and taking advantage of the delay by catching up on the development of the lunar module). But to outside observers, the disaster seemed to halt Apollo’s progress. To show the world it was capable of bouncing back and reaching the moon, NASA needed to demonstrate the safety of the command module in Earth orbit. This mission, the first crewed flight of the Apollo program, would be designated Apollo 7. Donn Eisele (pronounced EYES-lee) served as the mission’s command module pilot, testing out the guidance and navigation systems that would be critical in flying to the moon.

In terms of meeting its objectives, Apollo 7 was a major success. It got the space program back on its feet, proving the command module would work for the duration necessary for a lunar round trip. Yet the mission is often overshadowed by Apollo’s second flight, the Apollo 8 voyage around the moon. What’s more, the discussion around Apollo 7 typically focuses on the tensions that erupted between the astronauts and mission control. No-nonsense commander Wally Schirra delayed a planned television broadcast and defied mission control’s instructions for the crew to wear their helmets during reentry. His actions drew the ire of NASA management and ensured the Apollo 7 astronauts would never fly in space again.

Apollo Pilot, Eisele’s autobiography, fleshes out the story of the mission and of the men who flew it. In an afterword, his widow, Susie Eisele Black, notes that one of the best things about the book is that it “puts straight” many misconceptions about the forgotten flight, showing it for the successful mission that it was, rather than dwelling on the crew’s so-called “space mutiny.” But before talking in detail about Apollo Pilot, it’s important to talk about how this remarkable book came about.

Donn Eisele died in 1987 without having published an autobiography. Years later, drafts of a planned memoir were found among his personal effects. Eisele’s widow allowed British space writer Francis French to read the pages and edit them into a cohesive memoir. The resulting book was published in 2017 by the University of Nebraska Press as part of its series “Outward Odyssey: A People’s History of Spaceflight.”

This unique route to publication affects the book in a few important ways. First, possibly because they were in an incomplete, unedited state, Eisele’s observations are much more candid than those that appear in other astronaut memoirs. He bluntly talks about the rushed NASA schedules that led to the death of his friends in the Apollo 1 fire. He also sharply criticizes NASA manager Joe Shea and chief medical officer Charles Berry. Eisele writes plainly about the astronauts’ extramarital affairs, too, stating that “three-fourths” of those in the Astronaut Office engaged in such activities. All this may make the book sound like a salacious tell-all, but Eisele’s straightforward tone makes it feel more like a set of honest observations—perhaps the most honest of any written by an ex-astronaut. In fact, this honesty makes Apollo Pilot an invaluable resource in the Apollo library. The book may well be the least-filtered on-the-ground look we have at the astronaut experience.

Criticisms aren’t the only interesting subjects Eisele brings up. He also includes interesting discussions of space food, writing about the astronauts’ involvement in choosing the types of meals that would be included on their flights. One of my favorite passages was Eisele’s fascinating description of the sound of the spacecraft’s reaction control system (RCS) thrusters. These small rocket engines, mounted in four groups of four around the service module’s exterior, provided gentle thrust to pitch, yaw, and roll the vehicle. Eisele talks about how the pitch and yaw thrusters made distinct musical notes when pulsed, while the roll thrusters simply produced dull thuds. Vivid descriptions like these give the reader the sense of floating in the spacecraft right alongside the astronauts. Another delightful aspect of the book is the crew’s love of puns. Eisele relates many of their groan-worthy quips—and even the cantankerous Schirra gets in on the action.

As outlined above, the raw nature of Eisele’s memoir is a strength, but the book’s origins also have some downsides. Apollo Pilot is a relatively slim volume, clocking in at just over 100 pages, and there are points at which it feels like significant parts of the story are missing. I found myself wanting more of Eisele’s observations. This includes not just moments of the Apollo 7 mission itself—the helmet episode, so prominent in most retellings of the mission, is largely glossed over here—but also Eisele’s life before and after the mission. We learn little of his boyhood, and we don’t really get a sense of Eisele’s involvement in later Apollo missions. (Though he didn't fly again, he remained at NASA until 1972.) We also don’t get his reaction to the achievement of the lunar landing goal less than a year after his flight.

That said, French has done a great job stitching the discovered pages into a memoir, and the result mostly feels seamless. It isn’t clear exactly how much additional writing and reworking was involved, but I suspect that French may have added bits of context or explanations of technical terms. However the specific words came about, the book reads very smoothly, and it is accessible even for readers not already intimately familiar with the Apollo program. I deeply enjoyed Apollo Pilot—it’s truly exciting that such fresh material on Apollo 7 can be published nearly five decades after the mission’s foray into Earth orbit. I can only wonder whether other untold Apollo stories are sitting in dusty boxes in people’s attics or closets. If they are, I hope they’ll eventually receive the treatment that brought us Apollo Pilot.