Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys by Michael Collins

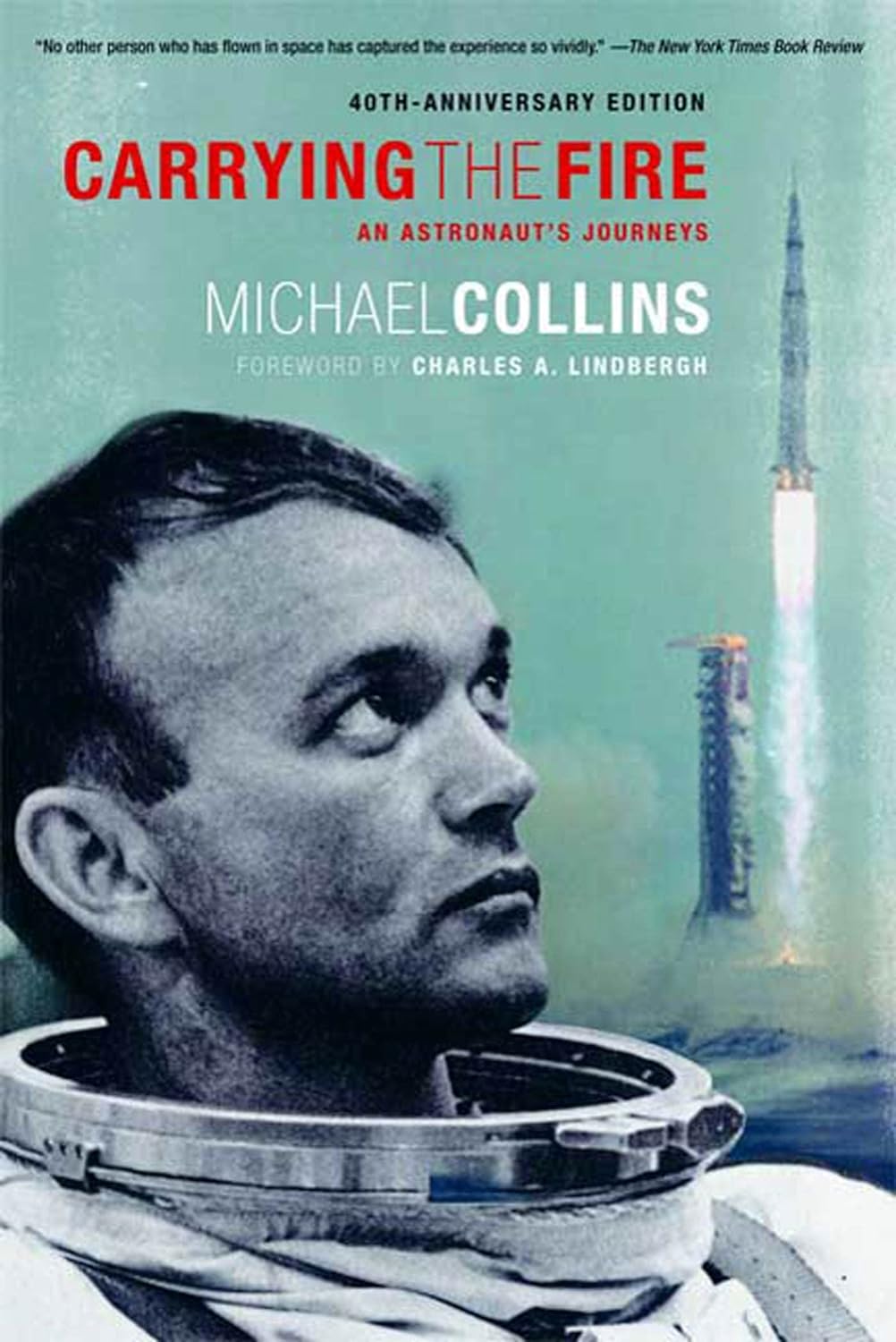

Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys was written by the Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins and published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1974. It’s an autobiography. I read the 2009 edition, which runs 478 pages. This edition is billed on the cover as the 40th Anniversary Edition (the anniversary is of Collins’ moon mission, rather than the book’s original publication). The cover is handsomely designed in grey, red, and black. Inside the book, there are three sections of black-and-white photos. The photos are well-chosen, and the tone of the captions fits perfectly with the humor and insight of the main text. A terrific foreword by Charles Lindbergh reveals the aviator’s fascination with space travel and allows him to speculate on man’s future in the stars. Collins is funny, candid, and a skilled writer. For me, this is the gold standard for Apollo astronaut biographies.

The memoir is heavily weighted towards Collins’ work at NASA (he becomes an astronaut by page 50), but the material prior, concerning his test pilot days and the astronaut selection process, does not come off as rushed. Though these elements are common to many astronaut biographies, they are told well here. Next Collins discusses his days in the astronaut corps before he is assigned a flight; the insights into training methods and astronaut input into the design of the spacecraft are highlights. The remainder of the book covers his two spaceflights: Gemini 10, his three-day orbital flight with John Young, and Apollo 11, the lunar landing mission.

One aspect that sets Carrying the Fire apart from other astronaut memoirs is that there is no “with” in the authoring credit. Collins wrote the book by himself, rather than through a ghost writer. In the book’s preface, he speaks to this: “No matter how good the ghost, I am convinced that a book loses realism when an interpreter stands between the storyteller and his audience”(xx). He’s correct. And fortunately, it turns out that Collins is a talented, thoughtful writer. He comes off in the book as a self-deprecating, ultra-competent, and simply likable personality. Complicated concepts such as orbital mechanics and platform alignments are explained lucidly, and he avoids the opposite perils of oversimplification and using dense jargon. He is also handy with an expletive or two: “...Houston responds with a description of the Houston Astros in a series with the New York Mets. Jesus Christ! Here I am asshole deep in a 131-step EVA checklist and they want to talk about baseball!”(219). To be clear, the entire book isn’t so colorful. But there’s just enough rough language to guarantee it isn’t a piece of NASA PR. The book is, in a word, genuine.

In a section near the book’s end, as Collins writes about the meaning of his trip to the moon, he gets into some territory that really grabbed my attention as a person who majored in both Communication Studies and Cinema Studies. He writes about the concept of “two moons.” Reason, he says, tells him that the moon he can cover with his thumb from Earth is the same moon he saw from an altitude of about 70 miles. But emotionally they remain two distinct entities. If this perspective shift fails to happen for a person who has actually visited the moon, what hope is there for the earthbound? After making reference to the notion that if world leaders could see the Earth from space, their perspective might change, he concludes that simply seeing the image of the whole Earth is insufficient. “Seeing the Earth on an 8-by-10 inch piece of paper, or ringed by the plastic border of a television screen, is not only the same as the real view but even worse—it is a pseudo-sight that denies the reality of the matter. . . . While the proliferation of photos constantly reminds us of the earth’s dimensions, the photos deceive as well, for they transfer the emphasis from the one earth to the multiplicity of reproduced images”(471).

This observation (as well as a sly reference to Marshall McLuhan earlier in the book) shows Collins’ keen understanding of the power and limitations of communications. The Apollo astronauts returned to Earth not just boxes of rock and dust, but also thousands of photographs and hours of film. Yet the images themselves are insufficient. Even more today than when Collins wrote, an image can be easily faked. No one blinks an eye at the science-fiction vistas plastered across today’s screens. There is hope, however. The profound images of Apollo can be appreciated by those who take the time to understand what made them possible. One way to do that would be to hand them a copy of Carrying the Fire). The facts behind the images are what make them important. Collins communicates these facts so expertly they compel you to review the images in a new light.