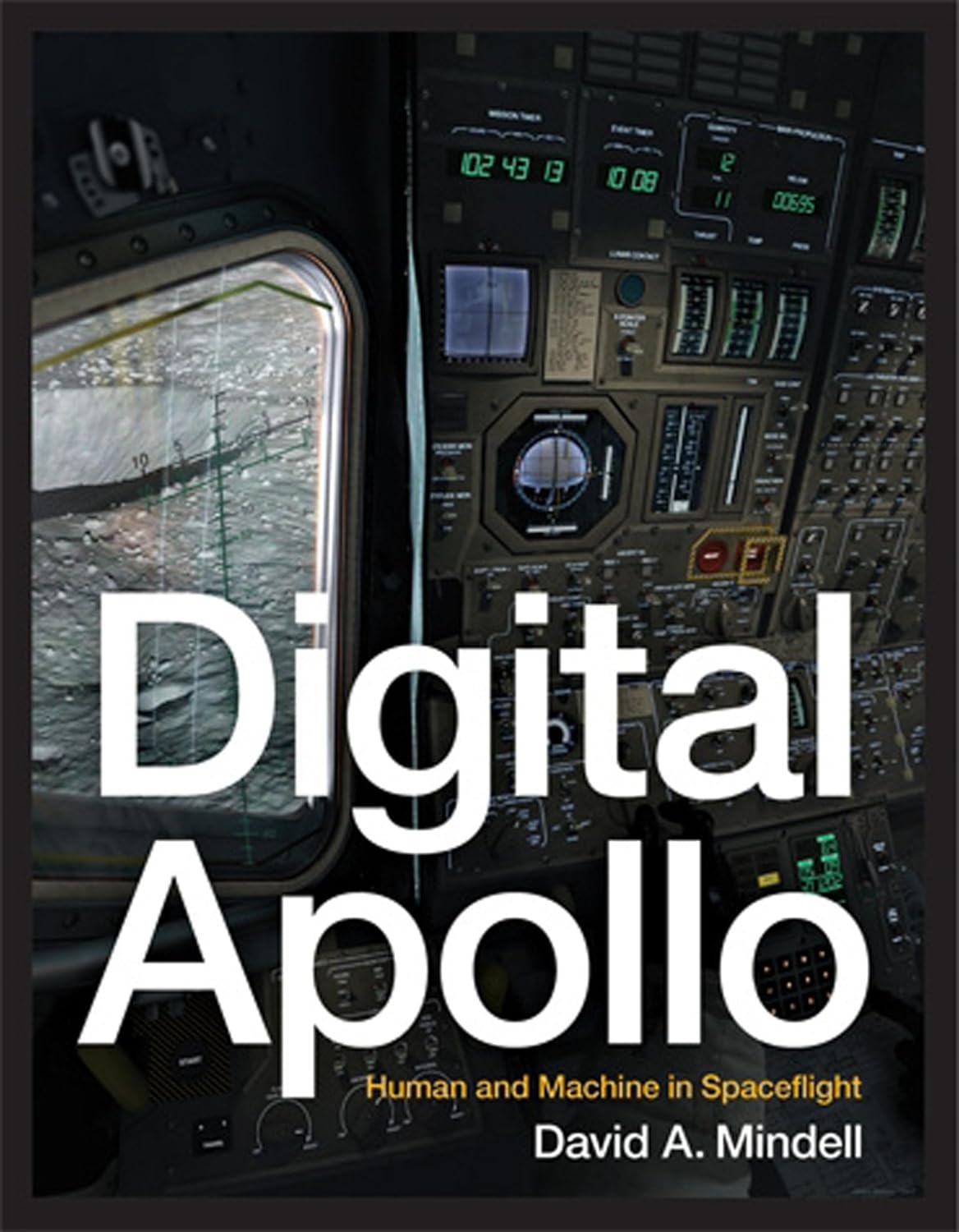

Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight by David A. Mindell

The Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) wasn’t a fast computing machine; it didn’t need to be. Above all it needed to be reliable, and it was. It needed to operate in deep space for two weeks straight, and it did. The astronaut’s lives depended on it, and it never suffered a significant failure on a mission. The AGC was the exact right computer for the job. Each mission had two: one in the command module and one in the lunar module. They differed in their software, with each spacecraft running the programs relevant to its role in the mission.

Following President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 speech asking the nation to commit to a manned moon landing by the end of the decade, the first Apollo-related contract signed was the one for the AGC. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Instrumentation Lab (IU) was responsible for it. Taking up about a cubic foot and weighing some seventy pounds, the AGC was state-of-the-art in terms of its combination of computing power and reliability. Astronauts would interact with it via the DSKY (display and keyboard) assembly, consisting of a numerical keypad and a set of seven-segment displays reminiscent of a retro alarm clock.

David A. Mindell’s 2008 book Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight examines the role of the AGC in the moon landings. At the book’s heart is the tension between automation and human control that emerged as NASA and its contractors developed spacecraft and mission designs during the 1960s.

On one side were the program’s engineers, many of them veterans of ballistic missile development projects. When building an ICBM, preprogramming a vehicle’s flight was the only option. These engineers preferred to involve the astronauts as little as possible, allowing the computer to execute the critical maneuvers needed to successfully complete a mission. (One joke among these engineers, Mindell reports, was that the astronauts’ job would be to simply use two computer programs over the course of a mission: one to fly to the moon, the other to fly home.)

On the opposing side were the astronauts. With their backgrounds as test pilots, they expected to be able to exercise active control over the spacecraft, controlling it as they would an experimental aircraft, getting to know the vehicle by feel. They hated the idea that without a piloting role, they would become “spam in a can.”

Mindell borrows terminology from the historian Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith to describe the two philosophies. One viewed the pilot as “chauffeur,” the other as “airman.” Originally used in relation to the attitudes of aviators in the early days of airplane flight, the terms are likewise well suited to the conflicts that later brewed in spaceflight. Mindell includes a great deal of historical context, tracing the history of the “airman/chauffeur” tension from early airplanes to the X-15 rocket plane to the Mercury and Gemini spacecraft. He centers his narrative around the lunar landings, and particularly the first landing, Apollo 11.

Neither side won a total victory; instead, compromise helped the program move forward. The pilots originally sought the ability to pilot the spacecraft not only during maneuvers in space, but also during the booster’s ascent. This rapid, violent phase of flight leaves little room for error and little time to react if something goes wrong. In the end, the pilots didn’t win this fight: the computers of the Saturn V’s instrument unit would control the rocket, and the astronauts would essentially ride it to orbit.

Still, the astronauts would have plenty to do. They would manually steer the command module and lunar module during rendezvous and docking. They would approve the computer’s ignition of the service module’s rocket engine by pressing the PRO (for “proceed”) key. They would input data and select new programs, making thousands of keystrokes in the course of a mission.

The landing phase of a moon mission puts the human vs. computer debate into sharp focus. During the planning of Apollo, the first landing was seen as the riskiest and most hazardous task the astronauts faced. They would be in an unfamiliar environment, piloting a machine that had never landed on the moon before. There would be no opportunity for a second chance, and tight fuel margins meant the astronauts would have little time to hover and fly to an ideal touchdown point. In the end, there was yet another difficulty on Apollo 11—Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin overshot their original landing area, so Armstrong was forced to improvise and quickly find a safe place to set down.

During a landing, the commander had the option to take total manual control over the landing, controlling both throttle and steering. But this fuel-inefficient option was never exercised. The computer was also capable of fully landing the lunar module on its own. This was never done either. Instead, every Apollo commander took semi-manual control over the lunar module during the final approach. They controlled the steering, but the throttle control was computer-aided. The commanders could set the desired descent rate, and the computer would adjust the rocket engine’s thrust accordingly.

The man-machine duality of the landings was also on clear display in the division of labor. The commander had his hand on the control stick and his eyes out the window as he steered down to the lunar surface. The lunar module pilot (note the misnomer—the commander, rather than the lunar module pilot, actually piloted the lunar module) had his fingers on the keyboard and his eyes on the computer display as he called out altitude and velocity rates for the commander. So in the end, the commander was still able to use his piloting skills, though he also relied on the computer’s assistance.

Digital Apollo is an enjoyable, illuminating overview of these issues. The historical context it provides regarding the “chauffeur or airman” conflict helps to explain how these questions were not unique to spaceflight, but in fact date back to the early days of aviation. The generous assortment of illustrations help provide visual reinforcement for many of the concepts in the book, especially those dealing with the complex interactions between the human and computer parts of Apollo. Many were redrawn by the author from NASA or MIT sources; the effort is appreciated, since these are generally crisply rendered and well-integrated with the text.

For me the highlight of the book is its narrative climax, when Mindell presents a nearly second-by-second account of the Apollo 11 landing. He provides the familiar dialogue between the astronauts and Mission Control, but along the way he also explains what the computer is doing and how the astronauts are interacting with it. The “you-are-there” quality of the writing here is wonderful, with details such as “Armstrong toggled a switch with his left hand, enabling P66” providing a glimpse of the physical action inside the lunar module’s cabin during the descent. Mindell weaves in postflight material, such as Armstrong’s later recollections of his thoughts during landing, to create a fuller narrative. This attention to detail and breadth of research is apparent throughout the book, but the landing of the Eagle is rendered in a particularly thrilling way.

For those interested in understanding how the moon landings worked, I highly recommend reading Digital Apollo. The book features not only a broad view of the philosophy behind computer use in Apollo, but also a close-up look at how astronauts interacted with those computers in carrying out their missions.