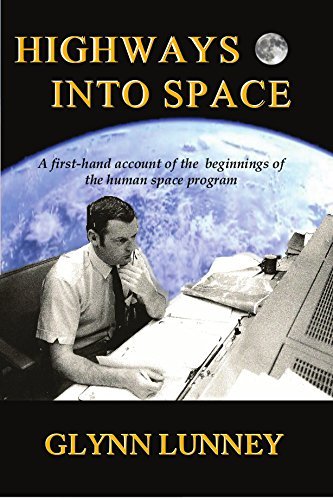

Highways Into Space by Glynn S. Lunney

Highways into Space has a great story to tell, but a lack of focus and polish makes the book come up short.

Written by Gemini and Apollo flight director Glynn Lunney, the book uses the standard format of the NASA employee memoir. It opens with an account of Lunney’s early life, moves through his entry into NASA, and presents a chronological recounting of Apollo that highlights his personal involvement with each mission. Lunney is best known for his role during the April 1970 Apollo 13 mission, when he came on duty as the flight director shortly after an explosion crippled the service module. He is perhaps less well known for a bigger role he played after NASA’s lunar landing program was complete. Lunney was the technical director for the United States during the Apollo/Soyuz Test Project, the mission in which an American Apollo spacecraft docked with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit. This job took up most of his time between 1971 and 1975, and it’s the focus of the book’s last third. Unfortunately, the book is marred by sloppy editing.

Highways into Space does have some things to recommend it. Lunney is a major figure in the Mission Control side of the Apollo program, and it’s useful to have his take on things presented in his words. The book gives the reader a deeper insight into the inner workings of Mission Control, making it a suitable companion to Chris Kraft’s Flight, Gene Kranz’s Failure Is Not an Option, and Sy Liebergot’s Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. The Apollo 13 story is well-told elsewhere, but the addition of Lunney’s perspective is valuable. The book also does a good job of giving the reader a sense of what daily life was like in and around Houston for NASA employees and their families. We hear about parties, barbecues, and after-work drinking sessions that help humanize the “steely-eyed missile men” of Mission Control. The social side of NASA isn’t discussed in such depth in many other sources, so I enjoyed learning more about it here.

Perhaps the most interesting material in the book is the behind-the-scenes account of the Apollo/Soyuz Test Project. The mission is discussed relatively little in the Apollo literature, so it’s great to have an in-depth look here. Flown in 1975, Apollo/Soyuz often feels overshadowed by the more prominent space events it fell between: the 1972 conclusion of the lunar landing program and the onset of the Space Shuttle era in 1981.

As technical director of Apollo/Soyuz, Lunney is in a great position to provide information about the mission. He discusses some technical insights into the hurdles that had to be overcome to make the docking possible, but he focuses much more on management issues, explaining how things such as language barriers and differences in working styles were overcome. He also provides a view of the politics and bureaucracy of the Soviet space program of the early 1970s. Some of the most fascinating parts of the book are Lunney’s accounts of traveling to the Soviet Union for planning meetings. Lunney emphasizes the elements of life behind the Iron Curtain that contrast particularly strongly with his experiences in the United States, and a number of funny anecdotes result.

The book has one severe problem: a lack of editorial oversight. These problems start on the most basic level. The book is rife with extra or missing spaces, misspelled names, and terminology that is either incorrect or used inconsistently. For instance, the author variously refers to the third stage of the Saturn V as the S4B, the SIVB, the S1VB, and the S-IVB (only the last one is correct). Acronyms are often not explained, or are only explained long after their first use. The construction of sentences is often awkward, stilted, or confusing. Information is frequently and unnecessarily repeated. At the same time, there is often not enough context or explanation provided for many of the basic concepts, systems, and missions. As someone who has read many Apollo books, I was mostly able to fill in gaps and follow along, but I suspect large chunks of the book would be hard to parse for a general audience.

Highways into Space feels as though it went straight from Lunney’s word processor onto the page. This actually may be close to what happened. The book is self-published, and there aren’t any indications that work was done by a self-publishing company, so it seems it was truly 100% self-published. There isn’t an editor credit given in the front matter. I wish Lunney had hired one—I suspect that the book is just a few in-depth editorial passes away from being really outstanding. It’s terrific that Lunney is willing and able to share his recollections on the program, but it’s too bad the book is not more polished. There’s lots of good info here—particularly on Apollo 13 and Apollo/Soyuz. Unfortunately, it was often a chore to wade through the prose and figure out what the author was trying to say.